The Truth Hidden Behind Lucky Families

The Truth Hidden Behind Lucky Families

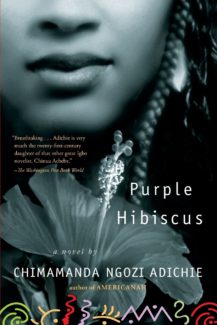

Author: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Another book club special, this time inspired by the One Maryland yearly selection, Purple Hibiscus is a complicated coming of age tale that focuses on self-identification in an abusive household. Fifteen year-old Nigerian Kambilli, from outward appearances, is living the life. While the rest of her country lives in intense poverty, Kambilli lives in a house that is downright palatial compared to the rambling hut of her aunt. Her father, the innocuously titled Papa, is not only wealthy, but revered. A strong Christian presence, he is a church elder who commands respect and discipline, a perceived savior who doles out everything from money to education for his worshipful flock. He is likewise a man of strong will and national pride, publishing a controversial newspaper, the only media outlet in a frightened country brave enough to speak against a corrupt government and advocate a different future. Papa is the paragon of his (and many surrounding) villages and if his rules seem a little strict at times, his Westernization a little too fake, his anti-Nigerian culture motif taken too far, his money and generosity fill the gap – at least for the outsiders.

Early on, we know something is deeply wrong. The entire household of quiet, respectful wealth is a simulacrum for destruction and fetid emotions. While Papa undoubtedly and confusingly has some truly “good” characteristics, including bravery to stand against a bribe invested government and risk his own life and well-being in the process, he’s far from being a stable character. The light in him has a violent and unpredictable antithesis – abuse that often verges into the terrifyingly violent. His demure wife and two children, Kambili and her older, more attuned brother Jaja, are serene out of necessity – the desire not to incite. As the novel opens with out-right rebellion by a disgusted teenage Jaja, the dark truth of the household is slowly revealed, sans flamboyance, signifying that to our narrator (Kambili) nothing is out of the ordinary or even worthy of notice. She does, after all, love her father who has a special ritual to share tea with her and whose strict approval means so much. If there is blood on the floor occasionally, bruises around her mother’s eyes, and a forced seclusion from others, that is merely the way things are for all families.

As Papa’s newspaper business grows increasingly more dangerous, he finally allows his children to visit their Aunty Ifeoma in Nsukka for a time. They’re sent off with the usual schedules dictating their hours of prayer, study, and conversation and given over with a strict understanding that they will not attend any traditional African festivals but, if going out, will only venture to church events or the reported local miraculous appearances of the Virgin Mary. Aunty Ifeoma, an outspoken professor at the University of Nigeria, however, has different ideas. As the stay extends and the forbidden pagan grandfather suddenly appears, Kambili and Jaja confront the full strangeness of their lives and Papa’s edicts. For the younger Kambili, this is the first time she has questioned her father’s authority – an uncomfortable betrayal of loyalty.

As Papa’s newspaper business grows increasingly more dangerous, he finally allows his children to visit their Aunty Ifeoma in Nsukka for a time. They’re sent off with the usual schedules dictating their hours of prayer, study, and conversation and given over with a strict understanding that they will not attend any traditional African festivals but, if going out, will only venture to church events or the reported local miraculous appearances of the Virgin Mary. Aunty Ifeoma, an outspoken professor at the University of Nigeria, however, has different ideas. As the stay extends and the forbidden pagan grandfather suddenly appears, Kambili and Jaja confront the full strangeness of their lives and Papa’s edicts. For the younger Kambili, this is the first time she has questioned her father’s authority – an uncomfortable betrayal of loyalty.

Purple Hibiscus isn’t your usual novel detailing growing up with abuse. The emotions are complicated, forgiveness and revenge catalogued in an inseparable almost symbiotic way. Adichie deals with life shattering topics in subtle, realistic ways that work to put the reader in the moment more than vivid descriptions of violence and feelings could ever do. It’s this manner of narration that makes Purple Hibiscus such an affecting novel, from beginning to end. It captures the transition from innocent youth to confused adolescence and embraces the problematic nature of human interactions. Surprisingly, Papa, despite the many horrors he perpetuates from outright violence to deliberate segregation of his family from potential friends and from their own culture (he speaks with a fake British accent after all and no Igboo, the native dialect of the region, is allowed to be spoken in his house or by his family), is not represented as an evil man. While the evidence of evil, perpetuated by shifting cultural alignment and his own internal demons, be they what they may, is obvious and always cloying, his goodness is something that also can’t be overlooked and this leaves readers mired in a real world quandary that many victims and abusers are trapped in. Papa does have such a thing as loyalty and while it can be pointed out that his contributions invoke endless praise – he is essentially treated as a deity– his willingness to risk it all and stand against an admittedly foul government leaves readers speculative. Papa is a brave man and one of principle, albeit often misguided. He does get some things incredibly right though and it’s trying to understand this person and his paradoxical composition of both the angelic and the demonic that makes Purple Hibiscus such an unforgettable, and uncomfortable, read.

While abuse is portrayed, we guess more than we see, keeping the novel from being graphic but still having the gut-punch effect as though we had seen, witnessed, and felt it all. Kambilli’s maturation also involves responsibility, finding her own faith and viewpoint, discovering affection sans violence, and finally meeting her long hidden family. Along with these discoveries comes both the “normal” coming of age experiences – an interest in boys, for example – and specific awakenings for someone such as Kambilli, a person effectively encased in a bubble and discovering the world with all of its unregimented yet tantalizing chaos at once.

While abuse is portrayed, we guess more than we see, keeping the novel from being graphic but still having the gut-punch effect as though we had seen, witnessed, and felt it all. Kambilli’s maturation also involves responsibility, finding her own faith and viewpoint, discovering affection sans violence, and finally meeting her long hidden family. Along with these discoveries comes both the “normal” coming of age experiences – an interest in boys, for example – and specific awakenings for someone such as Kambilli, a person effectively encased in a bubble and discovering the world with all of its unregimented yet tantalizing chaos at once.

As if this all wasn’t enough, tensions are brought to a boil by Papa’s actions, Aunty Ifeoma’s desperate decision, and an ever degenerating political climate. Adichie concludes with a bombshell revelation and a forced acceptance of liminality for Kambilli who ultimately embraces responsibility without ever having the answers or completely sharing the viewpoints of her raging sibling and broken mother. It’s a strange ending of forgiveness and love that demarcates how long lasting the roots of abuse are, how many generations are effected like toppling dominos, and how despite discovery of goodness, nothing can ever be the same again.

Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1616202416″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019