War, History, Meaning

War, History, Meaning

Author: Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace is the Everest climb of literature – the true quest only hardcore readers take (and pass). With its thousand plus pages and supposedly difficult language, it has haunted me for years. The ultimate challenge. Finally, I was ready.

The story opens just prior to the French invasion of Russia and the following Napoleonic wars, resulting in Napoleon’s final capture and then loss of Moscow. In between the famous general’s tactics, Russia’s failed military responses, and the revolt of the peasants to the ways of “gentlemanly” warfare, we follow both the romantic and existential crises of several major and minor figures. Here, the heart is just as much of a battlefield as the frozen plains outside Moscow, and the story alternates between the frontlines of the war, where several of our would-be heroes seek something more exciting and meaningful than the banal pleasantries of high society, to the behind the scenes stories, mostly (not always) of the wives, mothers, and lovers left behind.

There are a LOT of characters in War and Peace and true to the forms of classic Russian literature, most of them have several different names and nicknames. Their personalities and dilemmas, however, make them easier to keep separate and follow than in some other Russian classics (Brothers Karamazov for example).

For the major characters (at least those who resonated with me) we have first Pierre. Pierre is a bit of a social outcast, being born out of wedlock, only to have his fortune turned on its head by a dying old man with a spiteful will and testament. Suddenly finding himself rich and therefore accepted, however, hardly solves Pierre’s problems. He is just as dissatisfied as before, despite marrying a gorgeous and affluent woman, and his search for meaning takes him through the Freemasons and finally to the after-effects of Napoleon’s conquest, where an unlikely heroic movement puts him into extreme deprivation where, true to the glumness of Russian literature, he finally learns something about life.

Pierre’s story takes up a goodly portion of War and Peace. If I had to pinpoint a main character it would be Pierre, who oddly enough is more relevant to the peace portion of the book and not particularly militarily inclined. Pierre is at times sympathetic – he desires a fulfillment and knowledge that is all too human. At other times though, Pierre’s dithering and endless internal dialogues, plus the way he takes to a thing but is ultimately too inept to drive results (freeing his serfs, for example) makes him increasingly exasperating.

Meanwhile, Prince Andrei, Pierre’s one true friend, has fled a gorgeous socialite wife whom he can’t stand (Tolstoy goes on and on about her being a real beauty because of her mustache – I kid you not) and seeks meaning in the army. He leaves his wife behind, exiled from the social circles she loves, with his cruel father and kindhearted but isolated sister (Maria). Andrei is the opposite of Pierre. He is always seeking physical action and some new thing to give him glory. War is exactly what he needs – but is it everything he thought or hoped it would be? Will he even survive it, and if he doesn’t, does a brave sacrifice or a moment of bravery really mean anything?

Back at home, Prince Andrei’s retiring sister, Maria, is the antithesis to the bedecked socialites who swarm the best society and flaunt their beauty and worldliness. Maria wants only to escape her horrible father and find love or, baring her ugliness, take up a life as a traveling penitent/missionary. Maria’s story is interesting partly for the gross unfairness of her brutal father and partly for the lives she touches and the stories she becomes involved in. She’s also a living lesson that external beauty has nothing to do with internal beauty.

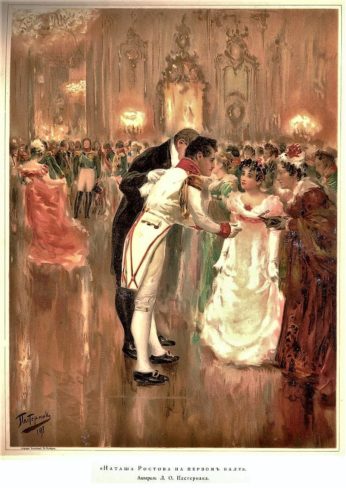

Natasha Rostova is a young girl, high on love. She is a second chance for Prince Andrei, but she is also impulsive and seeking her own form of excitement, which is the inevitable set-up for a fall from grace and a love triangle that eventually resolves in redemption and a disturbing slide into acquiescence.

There are many other characters, from Natasha’s ill fated brother, to Anatole (home wrecker and personal enemy of multiple characters), to the devoted and sluggish Sonya, to my favorite brief character, Platon Karataev, who shows Pierre beauty and contentment in simplicity while a starving prisoner.

As these characters come together, touching one another in various points of life, misunderstanding each other, falling prey to their own desires for excitement or meaning, the war starts to rage. We don’t get as many scenes at the front as I had expected, although there are a few moments of battlefield frenzy (and poor management). The war portion of War and Peace is mostly where Tolstoy stands on his soap-box and introduces the heart of his philosophies, while also giving readers a much-needed historical backdrop. Not being a history buff and having very minimal knowledge of non-US history, this was both helpful and intriguing (at times), but it was also a bit overwhelming since the characters and their problems became dwarfed by the universal meaning of war and Tolstoy’s prediction that history is inevitable: a character in and of itself that is the epicenter of fate in which we are all trapped. Tolstoy also likes to note that the way history is told and the real truth of what happened are entirely different things. In a way, history is told by the victor, but more than that, it is a lie espoused for numerous purposes from those of political intrigue to covering up embarrassing mistakes or duplicity.

Tolstoy hates Napoleon with a vitriol that is almost personal and definitely satirical. The “fat general” actually blunders into the plot a few times, a squalid little man who simply got lucky and, Tolstoy claims, was no great tactician or even a particularly intelligent dictator. Interesting.

Meanwhile, the really good stuff gets started as we walk through the failures of gentleman’s warfare and meet the Russian peasants, who show a pluck and courage that readers cannot help but admire. The peasants are tired of being the playthings of the aristocrats, who are abandoning cities en mass and piling cart after cart full of fancy furniture and goods while the regular people stay behind, doomed to starve and die. The peasants are also tired of being invaded by enemies – being the ones who are taken prisoner, killed, destroyed, or otherwise bent to the will of the new army. And here, scorched earth policy arises, to the chagrin of Russian military generals and Napoleon alike. Thus the fomenting of a kind of warfare and the first rumblings of a later rebellion.

I remember one of my favorite British comedy shows, Bottom, where the character Richie Richard sits down every night to red War and Peace before bed. The joke is that he has been doing this for years and is still in the first chapter. We watch him read a few words (not even a sentence) and then instantly pick up the Dictionary. And let’s be honest, this is what we all imagine when picking up War and Peace, even the intrepid classics readers. But, it’s really not like that at all. The writing is clear and accessible, very easy by classic standards, and more modern than a lot of other works (even Dickens). The difficulty comes in keeping up with the characters and the increasing insertion of essays on war and philosophy.

The first half of the novel is mostly character driven, but by the second half, Tolstoy has come into his own and the characters drop back, settled where they were left, as Tolstoy reveals his passion for history and his opinions on everything from the policy of the peasants to different Russian generals and the resulting gossip of which they were either fairly (or unfairly) subjected. This is a poor choice as far as plot is concerned, and readers are soon tired of war and ready to get back to peace, where most of the characters are languishing on the back burner. Tolstoy has a lot of beautiful (and some entirely unnecessary) things to say, and his characters and their dilemmas become an afterthought that is thrown into the epilogue (an enormous beast that lasts four hours in the audio book version).

And what an epilogue. Seeming to realize that some plot threads had been left untied, the epilogue goes through the “what ever happened to” modus operandi in a systematic and seemingly bored way. The vim and vigor of the people from earlier in the book is lost in summary.

Also, many of the endings are blatantly unsatisfying, especially Natasha’s conclusion. The fiery young girl succumbs to the jealousy of a bored wife, lets herself go, and becomes a devoted, disheveled mother, with none of her original personality intact. What is Tolstoy saying here? Is this the usual whore vs angel argument, or just a really sloppy ending?

Natasha’s is one of the more unsatisfying conclusions, but much of the epilogue pulls the supporting structures out and allows the good aspects of the novel to falter in a forgotten heap, an epically long P.S. intended to make up for the fact that half-way through the book, the author became more interested in writing about his philosophy of history.

And so, War and Peace was good, certainly easier than I expected, but hardly on par with some of Tolstoy’s other work, including his short stories and the unforgettable Anna Karenina. It’s certainly worth a read, and doesn’t deserve the severe reputation it receives, but it’s hardly my favorite venture into the classics, despite its more stellar moments.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”0143039997″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019