Morbid Ruminations…

Author: Dick Teresi

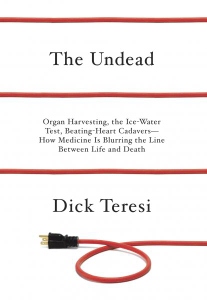

An aging journalist, Dick Teresi is going to die, just like the rest of us. Unlike most people, he chooses to spend a lot of time thinking about it. As he’s researched this topic, much to his chagrin, he’s learned that, while death happens to everyone, nobody – not even the most expert scientists, theologians or doctors – know how to decide when someone is finally and completely dead. Surprisingly, death is anything but straightforward, even though it happens  everywhere and every day. Rather than keep these ruminations to himself, Teresi feels compelled to share his findings in The Undead, an in depth exploration of what happens before we’re six feet under.

everywhere and every day. Rather than keep these ruminations to himself, Teresi feels compelled to share his findings in The Undead, an in depth exploration of what happens before we’re six feet under.

Teresi starts story with a discussion of how the definition of death has changed over time. From Egyptian mummification, which was meant to simply assist with the transition to the afterlife, to the understandable 18th and 19th century obsession with the avoidance of premature burial, he brings the reader to the modern day definition of “brain death”. Most of the book is spent exploring and questioning this last topic, which is anything but as simple or straightforward as one would like it to be.

After discussing various brain death definitions, finding their scientific basis and their clinical use both sorely lacking, the author seeks out some eyewitness testimony. He compiles numerous stories from people who have been diagnosed with conditions like persistent vegetative state or locked-in syndrome, in addition he visits a support group for people who’ve had a near death experience. Do these people help us understand what happens when someone dies? Can they help us define death more accurately?

Teresi seems genuinely distressed – and reluctant – to discover that death is not a moment, but an unpredictable process. In some cases, different parts of the brain and body often seem to die at different rates. When someone is severely ill or severely injured they may approach a point where the chance that they’re going to reverse the process becomes very small. In some cases they can even get stuck part way. How far along in the process does one have to get before we give up? How certain do we have to be in that determination? Who gets to decide?

Despite all the advances of modern neuroscience, there are many more questions than answers.

For anyone interested in thinking about death, these are fascinating topics, but in this book, lurking in every chapter – in every hospital hallway and on every street corner – are the transplant surgeons. They want your organs and they’re not necessarily going to wait for you to die completely before they take them. Teresi goes out of his way to make sure that we know that transplant surgeons are over-eager, arrogant, greedy bastards, waiting until the end of the book to concede that they perform about 28,000 life saving surgeries a year, when they can take a break from pompously counting their money.

Despite his writing skill and self-proclaimed journalistic objectivity, it’s Teresi’s withering assault on transplant surgery that stands out the most in this book. Without exception, the transplant doctors and nurses’ main goal is to get more organs to keep their coffers full of cash. It’s possible that I’m overstating it a bit, but it really appears that Teresi is suggesting that we wait for the one unequivocal sign of death before calling the transplant team. Decomposition. Until the body starts to smell, we can’t be entirely certain that death is irreversible. Personally, I’m ready to call it quits before then and if possible help others who could benefit from the use of organs I’ll no longer need.

Let me also say one last thing about arrogance. While I’m willing to concede that there is certainly such a thing as an arrogant transplant surgeon, it’s been a long time since I’ve read a book by such an arrogant author. That’s only my opinion and it may be partially due to fact that I disagree with his desire to eliminate organ transplantation, but I’ll present one piece of evidence that I think is particularly telling. In every science journalism books I’ve ever read, the author includes an acknowledgement of all the experts and specialists that assisted him or her. Not in this book. Apparently, Teresi thinks that he can sort out the many complexities of the human brain and critical care medicine all by himself, after talking to a few people and reading some articles, which may explain why his arguments are so lacking.

It goes without saying that life and death are emotional topics for patients – and their families – whether they’re organ donors or recipients. It’s also true that, despite Teresi’s statements to the contrary, the doctors and nurses who care for these people generally do the best they can. While any complicated system can have room for improvement and any journalist can find an example of where the system has failed, it’s also true that we’ll never have a definition of death that is without flaws. Despite the author’s claim that he’s just presenting the “facts”, The Undead chooses criticism over enlightenment and tarnishes the efforts that thousands of people make every day to try and extract life from an often tragic death.

— D. Driftless

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014

Leave A Comment