The Beginning of Masterton’s Best Loved Series

The Beginning of Masterton’s Best Loved Series

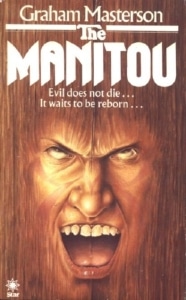

Author: Graham Masterton

Having been introduced to Graham Masterton’s long running Manitou series through the seventh, and most recent edition, Plague of the Manitou, I succumbed to addiction and went back to 1976 and Masterton’s first novel, The Manitou, which starts everything. Long a childhood favorite, Masterton has the unique ability to reduce readers to quivering mounds of fear, even veteran horror lovers such as yours truly. Recent additions such as Plague of the Manitou and the short story collection Figures of Fear have reawakened my Masterton admiration and blood lust for the delightfully macabre. The first novel Masterton ever wrote, I’ve long since heard of The Manitou but never been much of a fan of the synopsis. When Plague left me awake at night, cringing at all the creaks and groans of an old house, I changed my mind and happily purchased the book that started both Masterton’s career and the Manitou series.

Introducing Harry Erskine, the erstwhile fortune teller and grade-A cynic, the series combines humor, strong characterization, and gnawing horror. Things get freaky for our lovable charlatan Harry when a new client with an overnight neck tumor appears and gets a strange reading from his suddenly transforming Tarot cards. When the growing tumor is revealed as a fetus, doctors are shocked and horrified and Harry seeks the answers in the cards and the depths of the occult. Misquamacus, a powerful Native American medicine man from the 1700s is being reborn in Karen Tandey and seeking revenge for the brutal destruction of his people and way of life. Combining forces with Singing Rock, a current Native American medicine man, Harry is torn between sympathy for the villain and a desire to save Karen.

Kitschy, with more zeal than true originality, the plot exceeds in the uniqueness of its effort and is likewise harmed by the stereotypical horror elements it invariably falls back on. The later creeping horror and all out blood bath of Plague of the Manitou (and other books in the series, I am told) have the strength of time and refined authorship. Comparatively, returning to the first book is actually a bit of a jar, especially since Masterton has grown so much since the inception of his long running story. The idea is good, yet the delivery remains hackneyed here, stifled by a strange rapidity and a certain clinical description of unlikely events.

The characters are there, spot on in their warmth and realism, yet their actions seem scripted and the sudden decision to brave the inescapable wrath of spirits described as the equivalent of Christianity’s Satan not justified. Why does Harry go from lovable con artist to superhero, especially for someone he does not know? The terror is diluted then because of the scripted bravery and while readers want to wallow in the percolating Masterton atmosphere, the novel’s tentative expressions and desire to find itself gets in the way. It’s a good start, but compared with later work, it’s hard for fans not to nitpick. We’ve seen the fully developed product, after all, and what all those years of dogged work and writing have created. At this juncture, back in the mists of 1976, the creative juices are just starting to flow, and borrowing heavily from stereotypical horror norms.

Misquamacus uses Mantious, essentially powerful spirits that are neither good nor evil, which belong to all entities and objects, to do his bidding and wreak vengeance on his white conquerors. The only way to truly fight him is to use the white man “magic” yet again, by calling on the Manitou of a computer. . . . which is where I completely lose it. Just, no. While a viable option, this sudden discovery needs to be slower, more sinister, and less deus ex machina.

Nevertheless, while the birthing pangs of the series cause some serious eyebrow raising on behalf of the reader, especially fans acquainted with later Manitou vengeance, the introspection and sympathetic recognition of the Native American’s cruel slaughter and banishment from their own land creates a rage filled villain that, despite his amorality and terrifying powers, demands a certain sympathy and respect. Harry and Singing Rock, trying to save Karen Tandey and, effectively, the world, do converse to acknowledge Misquamacus’ right and even at different junctures contemplate saving the medicine man, if only they can do some damage control. It’s a deep notion and creates a talking point centerpiece that takes the drama outside itself to events of history and questions of ethics. The bittersweet ending with the “white man winning again” motif isn’t presented in victory or glory, but a certain sense of irony and a shadow of lasting guilt on the survivors. It’s not just your regular monster book, which is why despite the less refined elements, The Manitou earned its cult classic status, launched Masterton’s career, and started a series that gains credibility and intensity as the writing style matures, deepens, and becomes comfortable its own world.

- Frances Carden

Leave A Comment