Bad Morals, Charming Storytelling

Bad Morals, Charming Storytelling

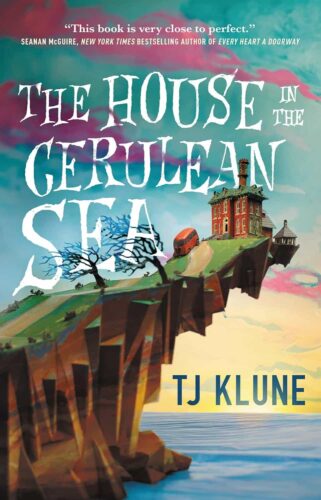

Author: TJ Klune

Linus Baker is the type of unassuming person who always colors within the lines. He does what he is told with precision, sheaves of paper, and a pedantic directness that has finally gotten him noticed. And that’s probably not a good thing.

Linus is a Case Worker at the Department in Charge of Magical Youth. He’s the bureaucrat sent to government-sanctioned orphanages to make sure that magical children are safe from one another and that society is shielded from them. That’s not to say that Linus doesn’t have a conscience. He does. But first off, he does his job. The system must be trusted. That’s before Extremely Upper Management gives him a classified assignment, where he travels to the orphanage on Marsyas Island, ruled by the enigmatic and dashing Arthur Parnassus. Arthur ignites something in Linus. Something that leaves him questioning everything. And the terrifying wards of Marsyas Island, including a five-year-old Antichrist who wishes death and destruction on the world . . . it’s possible that he just might be falling in love with them too. Perhaps Linus does not actually belong in a life where he draws and lives within the lines of the law.

The House in the Cerulean Sea is a deceptively comical book. It’s an adult Harry Potter mixed with a twinge of the dreariness of Office Space and some oddly cozy found-family moments. Linus is all alone in the world, and his city life is the kind where it rains every day, he never has an umbrella, and everyone at work is a grade-A bully. Linus is the gentle, awkward dude just trying to do his best and get by, armed only with a cat who doesn’t like him very much and a secret longing for something more from life.

When Linus arrives on the island, he’s greeted by threats. The Antichrist, Lucy, terrifies him. The gnome, Talia, threatens to kill him and bury him in the garden (repeatedly). The wyvern demands a treasure for the hoard hidden under the sofa. The sprite, Phee, gives him the cool girl brush off. The green alien blob, Chauncey, hides under his bed and won’t leave his suitcases alone, and finally, the were-Pomeranian, Theodore, lives in abject terror and dislike of Linus, transforming into a yapping dog at a moment’s notice. While the scenes are funny, there is a throbbing, odd darkness to the children. They’re violent, at least in their fantasies, and it’s downright weird that by the end of the book Linus finds these threats of death and dismemberment charming. Of course, by that time he has peeled back the layers of their personalities and gone beyond his job, learning to see the fear and isolation, the strong loyalty and love among the children, and the meaning of finding and fighting for a place in the world. Still . . . it’s just a bit weird to have kids threaten to compost your body in the garden every day and Lucy, the Antichrist, is just a little too sick to really be fully funny. I mean . . . he does kind of want to destroy the world. Does that bother no one?

Image by Aleksander Polanowski from Pixabay

As the book continues, I got drawn into the story, despite the weirdness. There is an insidious charm here, which does hide a pretty bleak moral. The story stands or falls on a terrible relativism, a philosophy hidden behind scenes of fun and love and magic, but nevertheless bleak and terrible. I couldn’t help but love the story, despite its undercurrents, but if you peel back the layer of charm and found-family, you’ll be repulsed by the squirming meaninglessness that festers underneath. We even get a scene of Lucy attacking a guy at a record shop, which is passed off as ok because the guy is Christian; admittedly, he WAS a jerk to a kid, but still, was the bashing necessary to the story? What was the author really saying here with the Antichrist-is-the-good-guy and evil-isn’t-really-evil theme? It’s a philosophy which, despite the patina of happiness and acceptance, actually thwarts everything this little family enclave stands for, but that’s a subject for another book, written by someone more articulate than yours truly. Just note that what the story stands for and what it is really saying are two separate things, and often that darkness and discordance peeks through, especially in the character of Lucy and the moments of “what-is-life” discussions between Arthur and Linus.

In the end, the story is told so charmingly that you put aside the darkness barely hidden behind the veil and root for Linus and Arthur and all the kids. You can’t help it. These people (and magical beings) become real, and to see the spark that had all but died in Linus come alive is heartwarming and magical itself. This is a strange little book, and surprisingly lives up to all the hype I heard about it once upon a time. Despite some philosophical issues I have with the moments where Arthur and Linus get all meaning-of-life, I still loved the story and the way it was told, even if I think the moral Arthur ultimately stands for is contrary to this love-and-acceptance-cures-all theme. This leaves me conflicted about actually recommending the book, so I leave that to your discretion dear reader. Five stars for storytelling, zero for moral theme.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019