A Surprisingly Banal Representation of Murder

A Surprisingly Banal Representation of Murder

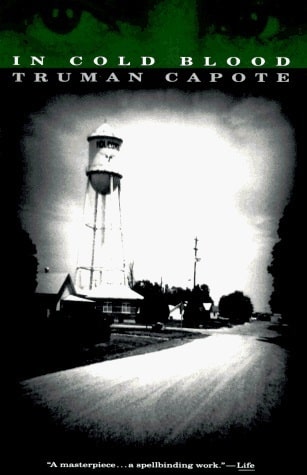

Author: Truman Capote

A sleepy Kansas town, where families safely leave their doors unlocked. Where everyone knows everyone else in town. A family – father, mother, two children, slaughtered in the night. Shot, point blank. Tied up. Robbed. All for $40.00.

Truman Capote took an infamous, seemingly inexplicable crime and ushered in narrative non-fiction and the popularity of true crime books with In Cold Blood, which has since become a classic. I remember as a child watching the first movie based on this book. I recall marveling at the complexity of emotion, the way that the two killers danced between decency and depravity, what it said about the human condition, about guilt, about true evil, about redemption. I also remember (and remain) being very afraid – this was a random crime, not one of passion, but one that involved a hapless family, living normally, who unwittingly became entertainment for two men. It is a true wrong place, wrong time story, with no clearcut answer, nothing we can learn to avoid the same fate.

In Capote’s telling, we start with the victims. The well-to-do Clutter family. The family was liked, was normal. Two daughters survived the infamous night because they were out with friends. The rest of the family was killed after many horrifying hours, after fear, after being tied up and treated like animals. But the true focus of the book (unlike the movies) is not the cold-blooded killings, but the mentality of the killers themselves. The focus of the story is the why – why did Perry Smith and Richard Hickock kill these strangers, and did these killers ever feel remorse?

Capote successfully shows compassion for both the killers and victims, while deep diving into the human condition. The question why, why, why beats through every page. Just as in the movie, there is no final answer, although here there is a lot more data. At times, far too much.

The Clutter home, March 2009

Spacini at English Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

While the movies were focused on the fear of the Clutters, the actual murders take a backseat in the book. Instead, Capote focuses on Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, their utter debasement and lack of empathy, their improbable dreams, and their stupidity. As with the movie, the focus is more on Perry, who is at first glance sensitive, even decent. The few “niceties” experienced by the dead Clutters were from Perry, yet he was also (supposedly) the one who did the killings, seeing them through only with an occasional wonder at what kind of person he and his compatriot were to do such a thing. “Is there something wrong with us?” was Perry’s occasional, casual query as the pair later lounged on a beach and read about the investigation, laughing and joking about what they had done.

While the movie is unforgettably brutal, the book has less of an impact despite its more detailed nature. This is because it spends way too much time tracking Perry and Richard before and after the murders, deep diving into every humdrum moment of their lives, from lying on the beach to examining run-down hotels to collecting broken bottles and hitchhiking. These non-essential, dull moments between Perry and Richard were, I think, intended to capture their essence, to wonder at the monstrous living side by side with the blandly normal. Instead, it became a testament to inexplicable research (really, how could Capote have the details on all these conversations) and plodding, unimportant moments that harmed instead of validated the book’s focus. As such, the narrative takes on the structure of a fictional tale oddly encumbered with the uneventful fluff and daily humdrum nature of everyday life. It’s sort of like being in the middle of a period drama, only for the director to pivot to a shot of a woman mopping the floor for forty minutes. Realistic, maybe. Necessary, absolutely not. Interesting? Again, no.

Image by Sam Williams from Pixabay

The final takeaway is both more complete and less satisfying than the movies. There is no mystery left. At the end of In Cold Blood, the book, there is nothing but two horrible people who deserved to be executed for their heartless crimes and inability to display any kind of regret or sadness. Their mocking laughs at the death sentence say more than enough about their state, their inability to be saved. Granted, both had terrible lives that might have led to their desensitization, but what happened to them was not unique, was not enough to explain what they became. The compelling question of the narrative is never really answered – what makes a person into a monster, nature or nurture? Why do some people, who have neither a good natural environment nor the support of nature, become kind, caring individuals whereas others become monsters? What is the tipping point, the magical formula? Why did these two men do what they did? Why did they remain so unaffected, so devoid of emotion? What made them suited to perform such a shattering, personal violation of a family of strangers? These are answers that we will never have, but in the end, I felt that the movies did a better job asking and framing the question and was ultimately more focused on substance as averse to style and fluff.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019