Violent fame…

Author: Norman Mailer

It was more than forty years ago, so long ago that Geraldo was still cool. But when it comes to the topic of capital punishment in the United States, 1977 was a pivotal year. Five years earlier, the US Supreme Court had stopped the practice, ruling that it was unfairly implemented as well as cruel and unusual. To many observers, it seemed like the death penalty was on its way out. Nonetheless, 37 states proceeded to write new laws and on January 17th, 1977, Gary Gilmore was executed by a firing squad at the Utah State Prison, the first execution anywhere in the US in almost a decade. The event gained international notoriety, even in literary circles, one result being The Executioner’s Song, an award-winning (and massive) novel by Norman Mailer. I’ll admit right up front that it’s a remarkable work, but is it worth reading now?

It was more than forty years ago, so long ago that Geraldo was still cool. But when it comes to the topic of capital punishment in the United States, 1977 was a pivotal year. Five years earlier, the US Supreme Court had stopped the practice, ruling that it was unfairly implemented as well as cruel and unusual. To many observers, it seemed like the death penalty was on its way out. Nonetheless, 37 states proceeded to write new laws and on January 17th, 1977, Gary Gilmore was executed by a firing squad at the Utah State Prison, the first execution anywhere in the US in almost a decade. The event gained international notoriety, even in literary circles, one result being The Executioner’s Song, an award-winning (and massive) novel by Norman Mailer. I’ll admit right up front that it’s a remarkable work, but is it worth reading now?

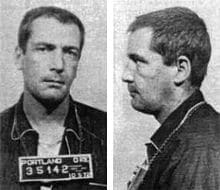

In and out of various correctional facilities since the age of 14, Gilmore was paroled in April of 1976 at the age of 35, moving to Provo, Utah to be near family. Continuing with countless criminal acts after his release, by July he had murdered two men without provocation. After he was sentenced to death by a jury in October, his case attracted widespread attention, particularly when he decided to waive any rights to appeal. Was he insane? The entire world was riveted as the man’s life hung in the balance.

Mailer divides the story into two parts. The first half focuses on Gilmore’s life leading up to his two-day murder spree and subsequent trial, emphasizing his tumultuous relationship with 19 year-old Nicole Baker. We learn much about the man’s perspective on life and his unremitting anti-social tendencies. The second half of the book describes how the world reacted to his sentencing, highlighting the response of the press to this potentially historic story of death.

Basing his chronicle on countless interviews, many of them collected by Gilmore’s attorneys while he was on death row, Mailer creates a remarkably convoluted web of family members, lovers, co-workers and criminals. Unlike some of his narrative non-fiction successors, Mailer himself is conspicuously absent from the proceedings, although his collaborator, journalist Lawrence Schiller, is the main character in the second half of the book.

One of the most disturbing aspects about the whole story was how quickly Gilmore – a violent monster by any standard – became an international celebrity. As the date of his execution approached, the press and the public were enthusiastically fawning over any salacious tidbits about the man. Mailer’s matter-of-fact chronicling of all the details serves more to observe, rather than fuel, these flames, but it’s still hard to avoid the feeling that Gilmore is portrayed as some sort of almost honorable anti-hero.

No matter what your view on the topic, this book is unlikely to change your mind about the death penalty. That clearly wasn’t the goal. It seems to me that Mailer’s main goal was to write eloquently about one of the most prominent news stories of the decade and maybe nothing more than that. In the process, he helped further the evolution of a new style of writing that was labeled New Journalism by its proponents.

As I read, I couldn’t help wondering what how the victims’ family members felt about the book? As Gilmore – who never voiced an ounce of remorse for his crimes – became an increasingly famous international celebrity, it’s hard to not to view a book like this as almost a celebration of the man’s life. Mailer does spend a small portion of the book telling the stories of Gilmore’s innocent victims, but the imbalance between their lives and their murderer’s saga is hard to ignore. If I was a family member of Max Jensen’s or Bennie Bushnell’s family, it would be hard not to hurt more because of this. I don’t really intend this to be a criticism of Mailer or this book, but more of a less than profound observation on human nature’s tendency to be fascinated with death and criminality. I like to think that a modern chronicling of events might have found a way to strike a more compassionate balance.

In the end, for a reader in 2018, the most important question is whether the book is worth reading today…

There’s no ignoring that it’s a daunting one thousand page challenge, but Mailer’s storytelling gifts make for a consistently smooth and intriguing journey. He deftly assembles an amazing web of interconnecting lives, generating tension with matter-of-fact prose, while eschewing flamboyance and pathos. Although it’s hard to identify many heroes in this expansive narrative, there are certainly a lot of sympathetic characters caught up in the increasingly turbulent events. The book is also an interesting look at the early days of narrative non-fiction, by an author who is widely regarded as an esteemed founder.

In hindsight, it’s not clear that Gilmore’s life story is of any greater significance than the violent creeps that have both preceded and followed him. The fact that no one has felt the need to revisit or reboot his story in the subsequent four decades is ample testimony to that fact. Near the end of the book, Mailer quotes journalist Barry Farrell to briefly make this point, by aptly describing the Gilmore story as nothing more than “mediocrity enlarged by history”.

So, I’m on the fence. It’s hard to say that Gilmore’s story is really worth telling or reading about, but I have to admit that Mailer’s efforts had me thoroughly engaged. I’ve certainly found myself thinking more deeply while reading and writing about this one book than I have during the half dozen that have preceded it.

Critically acclaimed both at the time it was published and since, The Executioner’s Song is often considered to be at the pinnacle of the true crime genre. It tells the story of a brutal man and his violent demise, but it also reveals how almost everyone else involved used this condemned murderer’s story to try and further their own goals, the author included. While Gilmore was never really much more than a violent and selfish blowhard, his story serves as an ample opportunity to take a broader – and less that flattering – look at humanity. A remarkable book no matter how you look at it.

— D. Driftless

Check out some of Dave’s other true crime reviews: American Fire / True Crime Addict / Lost Girls / The Book of Matt

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”B01N7NTVC1″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014