Horse Racing, Freedom, and History

Horse Racing, Freedom, and History

Author: Geraldine Brooks

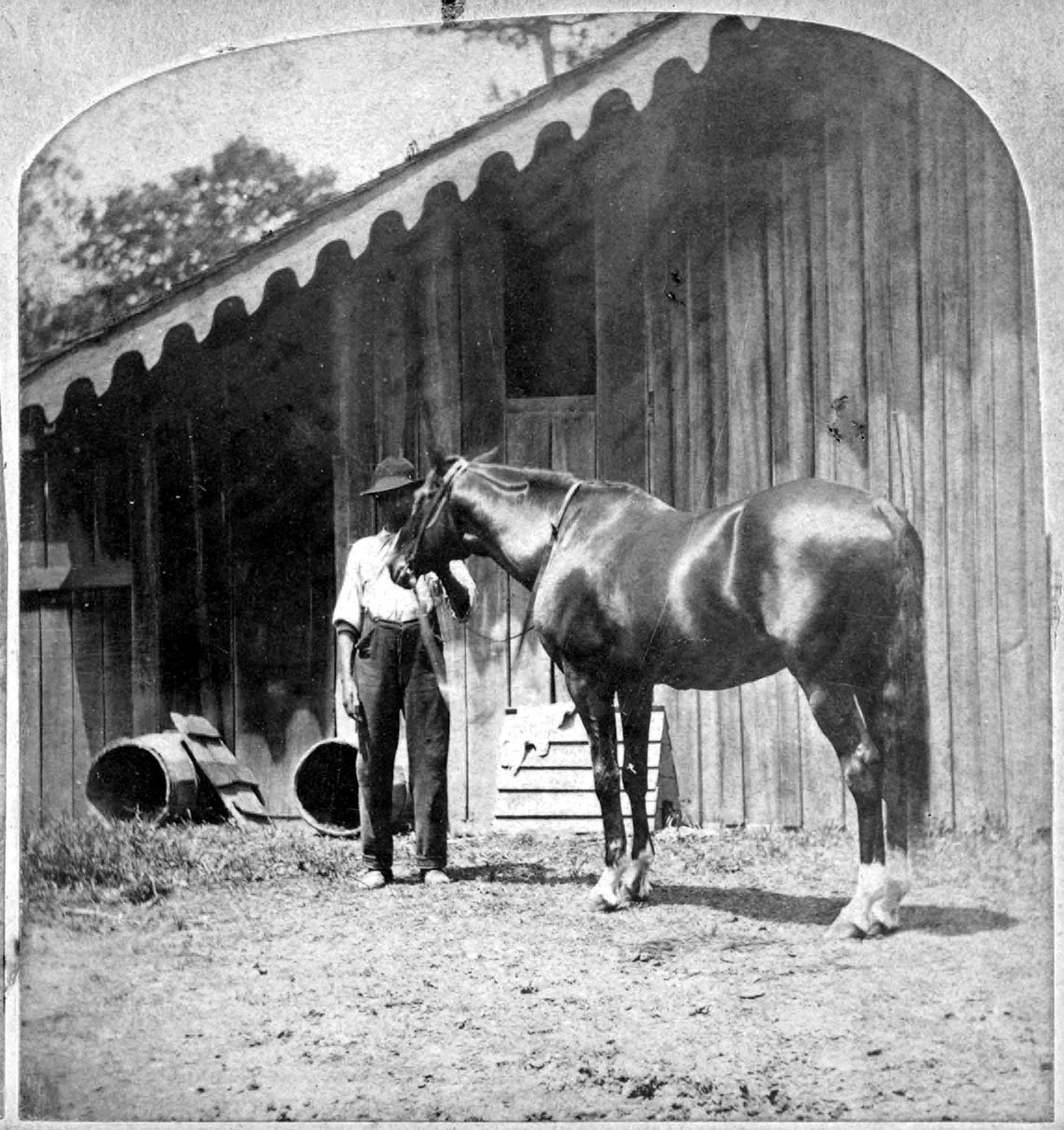

What do a record-breaking thoroughbred; a dusty, forgotten skeleton in a museum’s storage; a discarded painting; a thesis about a young artist’s depiction of Black grooms pre-Civil War; and a young couple’s tumultuous interracial relationship have to do with each other? In Horse author Geraldine Brooks oscillates between the past and the present to bring readers an epic story about horses and the fraught racial history of Black trainers and grooms in America’s history of horse racing. It’s a story with a huge scope, ranging from present-day Australia to Kentucky in the 1850s, jumping into the 50s to briefly visit Jackson Pollock, and tackling everything from racism, to police brutality, to the proper articulation of a horse skeleton, to the brutal life of horses raced for profit, to painting techniques, to moments in Civil War trenches, and more. There’s a lot going on. Some of it is beautiful and deep, most of it is periphery and sweeping. As with all of Brook’s books that I have read so far, the author takes good concepts and potential characters and sacrifices them for a cause, hurting the narrative by becoming heavy handed instead of letting her character’s experiences and perceptions translate to the readers.

Let me back up. After The Secret Chord and The Year of Wonders, I finally acknowledged that despite the fancy bestseller and prize winner badges on Brook’s works, which are always historical but cover vastly different periods and themes, Brook’s stories just aren’t for me. Her stories showcased good writing, but I was always aware that I was reading a story and that the author had an agenda she wanted to discuss. This left the characters feeling wooden and unreal, and regardless of whether I agreed with the author’s points (because there were always so many of them mixed together) I couldn’t ever accept the story as just that: a story. Horse is no different, but my new beloved book club selected it, and I am an animal lover, so I gave Brooks another try.

Of the three of her books I’ve read so far, Horse is my favorite, but it suffers from the same overwhelming and overbearing nature of Brooks’ other books. For one thing, half this book could go. We didn’t need the bit about the random doctoral thesis that never goes anywhere, we didn’t even really need the present-day romance, which was so self-conscious and awkward that readers felt the cringe. We certainly didn’t need Pollock, or that weird Civil War action sequence, or that strange moment where the artist starts talking about his sexuality which has zero relation to anything else going on. We didn’t need the topic of police brutality, thrown so casually into the ending as a bombshell, detonated without reason and with no where further to go. We needed the narrative to settle down on one topic, one theme, one all important thing to say. Instead, it’s a jumble of thoughts and ideas. They’re all serious topics, but we never get to spend the proper time with any of them.

Where the story soared was in the past, with Jarret. A slave from birth, Jarret is disillusioned and betrayed by everyone except Lexington, the colt with whom he has established a deep relationship. Jarret has a way with the horse, and through grit and skill, he manages to follow Lexington across the country, jumping from one master to another, all of whom use and dehumanize him in some way. The horse fairs little better, a plaything for masters more interested in dollar signs than the animal’s health. The relationship between Jarett and the horse is where the narrative shines, where it feels natural, where the character starts to come off the page. Jarett isn’t an idea (nor is Lexington for that matter). Jarrett’s a person, and because of this, the moral issues that surround his narrative (slavery, family issues, a connection with animals, education, North vs South and the prejudices of each) engage the readers and challenge us to face the horrors of history through the perspective of one human living through it and trying to find a touchstone somewhere along the way. Because Jarret is so real, because we can practically see Lexington’s coat and feel Jarett’s desire to ride her, the story becomes a story (most of the time – those weird horse rescue sequences toward the end were totally left field) and we feel and cry and rage against society and the injustices of life.

Everyone else though . . . all the other characters . . . they’re mere symbols. Some are more interesting or better drawn than others, but none of them are real. We see them as signs of a sermon we’re about to get, and instead of allowing readers to witness history and draw conclusions about the deprivations of the past and how many of them linger today, we’re just told. Not shown. This isn’t the clarion call to action I think the author intended, and in some places, it is barely even thought out, the author making points about Black characters (namely in paintings) being marginalized, only to do the same herself as a white author. It’s awkward, to say the least. And that’s only covering one of the ten thousand issues this book covers . . . which includes a weird statement about horse sex as art in the end. No, I’m not kidding.

Overall, Horse is more of the same from Brooks, but Jarret makes this story a bit more compelling than her other tales. He is a character that demands remembering against a background that throbs with some life, if only during the powerful scenes of horses literarily running for their lives. Still not a Brooks fan, but I didn’t hate this one either. If it wasn’t for my book club, though, I would never have read it, and even though I enjoyed moments of it, I won’t be coming back to Brooks.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019