This land isn’t your land…

Author: Steve Inskeep

Over the decades, there hasn’t been a shortage of stereotypes when it comes to depictions of the displacement of Native Americans from their homelands. From the civilized white Europeans taming the “uninhabited” wilderness to the savage and ignorant natives impeding the future of an entire nation, the clichés are plenty. But it wasn’t until I read Jacksonland by journalist Steve Inskeep that I realized how inaccurate these stereotypes actually are.

Over the decades, there hasn’t been a shortage of stereotypes when it comes to depictions of the displacement of Native Americans from their homelands. From the civilized white Europeans taming the “uninhabited” wilderness to the savage and ignorant natives impeding the future of an entire nation, the clichés are plenty. But it wasn’t until I read Jacksonland by journalist Steve Inskeep that I realized how inaccurate these stereotypes actually are.

As the United States rapidly spread from the Atlantic coast in the first half of the 19th century, white settlers headed into the southern terminus of the Appalachian Mountains, what would eventually become parts of Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia. Traveling west, they encountered native groups like the Choctaw, Creeks and Cherokee who had no interest in giving up their homelands. Ironically, many Cherokee had fought on behalf of the United States during the War of 1812. But once the frontier became more inviting to settlers, all prior alliances were forgotten. The state government of Georgia viewed it as the responsibility of the federal government to clear the natives out of the way, by whatever means necessary.

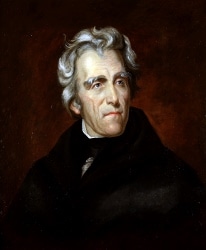

It is this frequently violent clash of cultures that is the focus of Inskeep’s penetrating historical gaze and he brings the story to life by focusing on two men: famous general and eventual US President Andrew Jackson and his sometime nemesis and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation John Ross. In what would eventually culminate in The Trail of Tears, the author tells of these two men, both shrewd negotiators and politicians who were also heroes to their respective people.

While the competition has been ramping up lately, I think it’s safe to say that Andrew Jackson still belongs near the top of the list of biggest presidential arseholes in US history. Not that the voters didn’t love him for it, but in hindsight it’s hard to view his genocidal contributions with anything but revulsion. Delving deeply into the back story of the first president with no connections to the American Revolution, Inskeep explores the man’s key role in clearing the natives from the southern states. From treaties that weren’t worth the paper they were written on to his refusal to rein in the open hostilities of his citizens, Jackson comes across less a presidential hero, more a fascinating, at times openly corrupt, creep. But for better or worse, he clearly had a profound impact on his young nation’s future and Inskeep makes it clear that his story is well worth close study, particularly since so many of the issues he faced and flames he fanned are still with us today.

In contrast to his less than flattering portrayal of the seventh US president, Inskeep tells a more uplifting story when he describes an American hero that most readers probably haven’t heard of. More Scottish than Cherokee – you have to go all the way back to his maternal grandmother’s mother to find a full-blooded Cherokee ancestor – John Ross was raised in both the European and Cherokee worlds. This served him well as he matured to become the leader of his Cherokee brethren, allowing him to nurture alliances on both sides of the cultural chasm. Although, the author makes it clear that the divide wasn’t as profound as it is often portrayed. Many of the Cherokee were wealthy business men – often slave owners – who raised crops and developed the land just like their white American neighbors.

After reading this work, I have to say that it’s hard to sustain any fondness for the state of Georgia – at least the 19th century iteration. Insistent upon gobbling up every last acre of land to the west, the white Georgians frequently had a tantrum if any limits were placed on their territorial designs. Foreshadowing the eventual War Between the States, Georgia repeatedly threatened to secede if the feds didn’t support their every desire. Just as foul in their treatment of Native Americans as they were in their abuse of enslaved Africans, the Georgians come across as rather monstrous spoiled brats, with echoes that resonate into the present day.

Returning to the arsehole theme, Inskeep does a nice job of exploring the moral issues that are such an important part of this story. Not content to play the role of apologist by letting Jackson get away with being a racist arsehole by claiming that everyone was a racist arsehole back then, the author presents the efforts of many white Americans who supported the Cherokee in their quest to preserve ownership of their homelands. Much like the slavery abolitionists and the anti-war pacifists of the time, there were plenty of Americans who recognized a crime against humanity when they saw one. Although, this liberal Yankee doesn’t find Inskeep’s final words on the matter entirely satisfactory, you’ll have to see what you think for yourself.

Tragically, it’s just another example of a president on the wrong side of history. In Andrew Jackson’s world, even “civilized” Cherokee who were sophisticated enough to farm their lands, learn English and even own slaves were not fit to be part of the United States of America. Organized enough to repeatedly send their representative John Ross to Washington to plead their case for more than a decade, these native-born Americans were told that nothing short of removal was an option. In Jacksonland, you’ll find a thoroughly engaging exploration of this pivotal – and often tragic – time in early US history by a master storyteller. Highly recommended.

— D. Driftless

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1594205566″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014