An American Serial Killer, a Confession, and a Sociopath’s Thoughts on Justice

Authors: Thomas E. Gaddis and James O. Long

“In my lifetime I have murdered 21 human beings. I have committed thousands of burglaries, robberies, Larcenys, [sic] arsons and last but not least I have committed sodomy on more than 1,000 male human beings. for all of these things I am not the least bit sorry. I have no conscience so that does not worry me. I don’t believe in Man, God nor devil. I hate the whole damed [sic] human race including myself.” ~ Carl Panzram

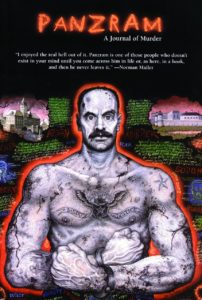

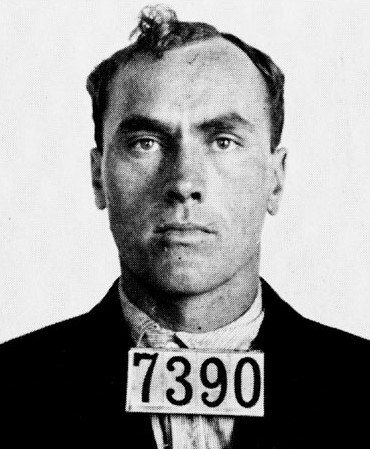

These sentences, scrawled on the back of Panzram: A Journal of Murder,with its weirdly lurid cover, captured my interest, and I had to read the book. Panzram is an American serial killer, born in 1891 and hung at Leavenworth prison in Kansas in 1930. His last words were the perfect testament to a life lived in sheer, animalistic rage.

“Hurry it up, you Hoosier bastard! I could hang a dozen men while you’re screwing around!” ~ Carl Panzram

This book ostensibly follows Panzram’s own written, autobiographical confession, promising to dove-tail into his murderous rampage across the United States and continual jail time, starting with thieving at age five and building towards twenty years, on and off, in various correctional facilities and jails. Panzram, as far as we know, only ever had one confidant, a guard named Henry Lesser who built a strange bond with the enraged criminal and received his written manuscript, carrying the burden of Panzram’s story long past the man’s death on the gallows. That’s how this book came about, half guilt offering from the author who was entrusted with Lesser’s quest and Panzram’s final writings and half introspection on the general penal system and its abuses and failures.

Panzram himself, serial murder and rapist, concentrates most of his epistles to Lesser on talking about how society made him a criminal, specifically through the failure of penal institutes, than in dredging up the sensationalistic details of murder and sodomy that the lurid book jacket uses as a hook. What you get then is a serious, if repetitive, psychological study of a criminal who, himself, has an odd tendency to introspect while never giving ground and a dossier on prison history, from the early 1900s juvenile reformatories with their crooked masters and torture to the creation of Leavenworth and brief, unsuccessful individuals who sought and failed to make a lasting change, specifically those who tangled with Panzram.

Is it unnatural that I should have absorbed these things and have become what I am today, a treacherous, degenerate, brutal, human savage, devoid of all decent feeling, without conscience, morals, pity, sympathy, principle or any single good trait? Why am I what I am?” ~ Carl Panzram

Gaddis and Long, the authors, supplement Panzram’s own writings, which are presented unadulterated but (I suspect) incomplete, with additional details of his history. No one really tells the story better or truer than Panzram himself, with his voice so resonant of hatred that readers shy away from its bluntness, cruelty, and appalling sacrilege. He was shocking in his time; and he remains shocking in ours. The writers often only sample from him though, doing the boring history book routine and pretending like they can fill in the blanks of a man who acknowledges himself a monster, claims his goal is to eradicate the human race, openly renounces Christ and wishes to crucify him again, and desires to be killed himself. This is a mistake, because in this Journal of Murder, as it is inaccurately titled, Panzram rapidly takes a back seat as the authors try to jostle the details of his past, Lesser’s simultaneous work through the penal system and his weird tie to Panzram, and the history of the various prisons and their leaders that host the killer, with the occasional dip into the unsuccessful publishing story of Panzram’s confession.

“I grabbed him by the arm and told him I was going to kill him. I stayed with the boy about three hours. During that time, I committed sodomy on the boy six times, and then I killed him by beating his brains out with a rock… I had stuffed down his throat several sheets of paper out of a magazine. I left him lying there with his brains coming out of his ears.” ~ Carl Panzram

The book moves away from what I think is the strongest pull of true crime, the ask behind the voyeuristic curiosity, that universal query: what makes someone evil. The answer is the system, at least as far as the perplexed authors can follow it, and so we spend most of the book focusing on the admittedly failed penal set-up and following Panzram during his final prison years. His horrors are (mercifully) a blip of the story, and the rest of the time he longs for death and opines on prison set-up and the cruelty of the treatment, with a few weird end chapters about, of all things, patents on fruit drying. The book is more about the prison system than about the serial killer who is suspended in the middle of it, and the focus is ultimately more academic without any real meat – there is speculation, namely by Panzram, but the conversation ends when he does.

Leavenworth Penitentiary

By Americasroof – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8727865

“I look forward to a seat in the electric chair or dance at the end of a rope just like some folks do for their wedding night.” ~ Carl Panzram

In the end, Panzram defies the people around him seeking to stop his death and show the mercy that many thought was the answer to this hard man. He showed no desire to reform and stated so. He got his life’s greatest wish: death. He went out much as he lived: enraged, violent, sacrilegious, unrepentant, glad to embrace death and wishing to give it to others. It’s a strange life to look at, an odder one to digest and understand. Many have gone through tortures equal and even greater, yet few have become a Panzram and there is no revelation here to the inner workings of a dead man walking. The system certainly betrayed him at every turn and helped to transform him into a monster – yet there is more to the making of such a man. Things, I suppose, we can never really know or, if we knew, understand.

It ends with a weird back-story by the author, a sort of tribute, debt-paid to Lesser, an acknowledgement that the author didn’t want to write the story, got distracted by several other stories, and out of guilt finally finished this one. This explains the lack of passion behind the narrative, that thing that is missing in what should be a dynamic discussion about how to punish without going too far, without creating and abetting monsters, while using the very eyes and perceptions of the monster to describe what he feels made him so. We leave it wondering why Lesser never wrote the book, why the obvious choice, the person who shaped his life around mercy and reform, and finally gave up, who carried the albatross of this weird story, never gave it the final say.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1878923145″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019