The Children Are Now Tyrants

The Children Are Now Tyrants

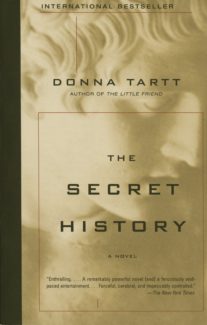

Author: Donna Tart

My first experience with Donna Tart has left me mesmerized, both by the art of her authorship and the casual depravity she reveals in humanity. The story is your typical college dysphoria. The haves and the have nots. The cool and the underdog. The campus weirdos and the elite in-crowds. How they all combine is where the story flowers, and what a dark and blood tinged flower of adulthood this story becomes.

Richard Papen is a poor boy from a lackluster, strip-shopping center California life, newly escaped to the semi-ivy league Hampden College in the atmospheric Vermont. This is his chance to raise above an upbringing that while never distinctly tragic is still loathsome to his sensibilities. Enter the campus outcasts. The Greek students who march to their own rules under the lustrous professor, Julian Morrow, who only takes students if he can have their all – their entire syllabus and a strange pagan sort of devotion. While the party girls and the frats like Ricard well enough, he senses that the wealthy egotism of this hard to reach enclave is where he should, where he has always, been made to belong.

Before long, however, the strange characters merge into a tragedy greater than their individual parts. There is Henry Winters, the giant of the group. The loaner, the Solomon-like visage they all scuttle under when the nearly divine Julian is not around. Francis, the wealthy (allegedly homosexual) loner with the far away country house and a penchant for billowing black coats and elegant suits, and then the twins, Charles and Camilla Macaulay, who work together as an oddly beautiful unit. It doesn’t hurt that Camilla is attractive, ethereal in the fierce boned way of a Valkyrie coated with a fake sort of innocence, a wide eyed worldly look that can take bloodshed in with as much ease as watching a flower coaxed out of the soul. This then is the soulless yet entrancing world Richard wants. And he gets it.

Before long, however, the strange characters merge into a tragedy greater than their individual parts. There is Henry Winters, the giant of the group. The loaner, the Solomon-like visage they all scuttle under when the nearly divine Julian is not around. Francis, the wealthy (allegedly homosexual) loner with the far away country house and a penchant for billowing black coats and elegant suits, and then the twins, Charles and Camilla Macaulay, who work together as an oddly beautiful unit. It doesn’t hurt that Camilla is attractive, ethereal in the fierce boned way of a Valkyrie coated with a fake sort of innocence, a wide eyed worldly look that can take bloodshed in with as much ease as watching a flower coaxed out of the soul. This then is the soulless yet entrancing world Richard wants. And he gets it.

As Richard slowly gains the confidence of his new friends and further distances himself from the regular college shenanigans, a greater darkness emerges than the midnight rituals and plays at paganism. Something happens. Something bad and yet, to those involved, oddly transcendent. Only Richard can judge them and this is, ultimately, his choice to reject a life where things such as murder are condoned as long as the proletariat – the intelligentsia – are the ones doing the killings.

From here the story spirals, the ranks close and open. The disagreements and petty betrayals and blackmail attempts take this group of friends, people who were never friends in the way we innocuously understand the world, and slowly devolve them beyond their lofty intelligence and into their animal instincts, which, really is what they have worshiped all along.

Along the way you never like or sympathize with any of the characters. Their coldness is off-putting, their elevated selfishness unable to be explained away by their fancy Greek and their ancient quotes. And yet, for all that, they are terrifyingly understandable. We’ve all met these sorts. Perhaps not with quite this much old style estate money, but the false intelligentsia who thinks they are better thanks to their book learning yet remains in a distinctly pre-civilized state. A murderous, reactionary, sociopathic sobriety that compels our interest while sending us, terrified, to the other side. Yet, but for the grace of God. . . We’ve all at different times been drawn into toxic friendships, into situations that seem only mildly bad and easily ignored but soon, and rapidly, go towards evil.

Along the way you never like or sympathize with any of the characters. Their coldness is off-putting, their elevated selfishness unable to be explained away by their fancy Greek and their ancient quotes. And yet, for all that, they are terrifyingly understandable. We’ve all met these sorts. Perhaps not with quite this much old style estate money, but the false intelligentsia who thinks they are better thanks to their book learning yet remains in a distinctly pre-civilized state. A murderous, reactionary, sociopathic sobriety that compels our interest while sending us, terrified, to the other side. Yet, but for the grace of God. . . We’ve all at different times been drawn into toxic friendships, into situations that seem only mildly bad and easily ignored but soon, and rapidly, go towards evil.

What also works here is the beauty of the language and the foreshadowing that creates tension. Tartt plays with time. There are drawn out periods of quiet before the storm. And then there is the escalation of the devolution, the secrets and the more than obvious there-is-no-honor among thieves fallout. It’s a sordid book really. What happens, who is involved, the casualness of truly evil people. Yet it is so well painted. So tragic in its own Greek way, and its point about those types of people who hide purely behind the mind is unmissable. In the end, each page is a breathless treasure, the story carrying us along irresistibly. This is one of the few books where I hated, viscerally, all the characters yet couldn’t let go and didn’t want to leave the world. This was partly due to the plot and where it went – and it went all the way – and partly to the beauty of the language and that (probably not intentional) message about evil and selfishness parading behind social superiority.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1400031702″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019