Maybe I’ve got multiverse myopia…

Author: Sean M. Carroll

It’s gained a certain notoriety. In the public eye, quantum physics has become virtually synonymous with the bizarre. It’s so weird, that even its most prominent proponents often admit that they don’t really understand it. They may even go on to accuse their colleagues of being mistaken if they claim they do. Maybe there is nothing as bizarre as the idea that every time some quantum event occurs at the subatomic level, the universe splits in two, creating endless replicas of every animate – or inanimate – thing. The idea that there are infinite copies of oneself spread out across the multiverse has served to stimulate the public’s imagination as vividly as anything Copernicus or Einstein ever envisioned. It’s an idea that is almost impossibly incomprehensible. But maybe it doesn’t have to be this way. Attempting to make the bizarre more understandable, celebrity physicist Sean M. Carroll presents his take on it all in Something Deeply Hidden.

It’s gained a certain notoriety. In the public eye, quantum physics has become virtually synonymous with the bizarre. It’s so weird, that even its most prominent proponents often admit that they don’t really understand it. They may even go on to accuse their colleagues of being mistaken if they claim they do. Maybe there is nothing as bizarre as the idea that every time some quantum event occurs at the subatomic level, the universe splits in two, creating endless replicas of every animate – or inanimate – thing. The idea that there are infinite copies of oneself spread out across the multiverse has served to stimulate the public’s imagination as vividly as anything Copernicus or Einstein ever envisioned. It’s an idea that is almost impossibly incomprehensible. But maybe it doesn’t have to be this way. Attempting to make the bizarre more understandable, celebrity physicist Sean M. Carroll presents his take on it all in Something Deeply Hidden.

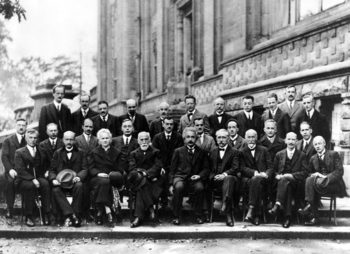

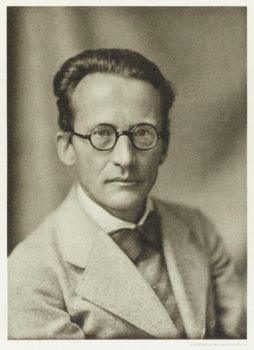

Carroll argues that physics has been in an existential crisis since 1927, when quantum theory was fully formalized by giants like Schrödinger, Bohr, Heisenberg and Einstein. Since that time, seemingly due to a lack of resolve, given their prior comfort with the logical world of classical physics, scientists have perpetuated the idea that the classic approach – developed by Isaac Newton way back in 1687 – applies to macroscopic things like humans, trains and solar systems. They’ve restricted the more troublesome quantum approach to the subatomic world of electrons and photons, creating a curious dichotomy within their theoretical approach to the world.

Carroll is trying to promote a more honest approach, recognizing that the universe is truly quantum from top to bottom, from neutrino to galaxy. Like a dirty secret, physics has spent the last 90 years pretending that this hard truth doesn’t really exist. They’ve often spent much of that time ostracizing physicists who chose to strive for a deeper understanding of quantum theory’s underpinnings. Much of Carroll’s effort is devoted to correcting this injustice by promoting the work of Hugh Everett, who first proposed the Many-Worlds (aka multiverse) theory in 1957.

While I respect Carroll’s motivation and he certainly has gone to great effort here, I don’t think he succeeded in clarifying much for me. I think that the blurbs on my hardcover library copy were an ominous clue. When every blurb on a book is from an esteemed physicist or mathematician you might have a problem. There are seven of them on the back cover of the edition I read, and I’m not surprised that they understood the finer points of Carroll’s work; they’re not mere mortals like the rest of us. But there’s not a single blurb from an ordinary reader, which should have clued me in. This was going to be some tough reading. In the end, I do feel that I learned something about the idea of an infinitude of multiverses, helping the concept make it one step closer to plausibility in my mind. However, I think much of Carroll’s explanatory effort fell flat, making the book more struggle than pleasure. I have to politely opine that I’ve enjoyed Carlo Rovelli’s books much more than this one.

It’s undeniably curious that despite the fact that the details of quantum theory remain so thoroughly mysterious, scientists manage to use quantum mechanics to do all sorts of things every day. Even though Something Deeply Hidden didn’t quite work for me, I have to respect Carroll’s effort to bridge this oddly stubborn gap between full scientific understanding and practical utility.

— D. Driftless

Check out my more enthusiastic reviews of Carlo Rovelli’s books: Seven Brief Lessons on Physics / Reality is Not What it Seems / The Order of Time

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1524743011″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014