The anti-Bond…

Author: Andrew Lownie

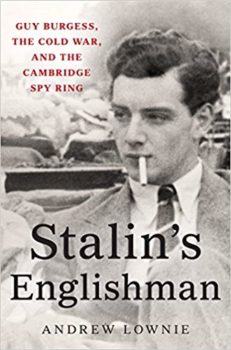

He may have been one of the more bizarre characters in British history. And that’s saying something. If you were to create a fictional character as foul and decadent as Guy Burgess, it’s likely that you’d be accused of excess and exaggeration. One of the Cambridge Five – a loosely organized gang of Brits who spied for the Soviet Union – Burgess gained notoriety when he disappeared in May 1951. When he eventually resurfaced in Moscow five years later, it became clear that he’d been spying for the better part of two decades. Published in 2015, Stalin’s Englishman – by biographer Andrew Lownie – is the first full accounting of the man’s curiously entertaining life.

He may have been one of the more bizarre characters in British history. And that’s saying something. If you were to create a fictional character as foul and decadent as Guy Burgess, it’s likely that you’d be accused of excess and exaggeration. One of the Cambridge Five – a loosely organized gang of Brits who spied for the Soviet Union – Burgess gained notoriety when he disappeared in May 1951. When he eventually resurfaced in Moscow five years later, it became clear that he’d been spying for the better part of two decades. Published in 2015, Stalin’s Englishman – by biographer Andrew Lownie – is the first full accounting of the man’s curiously entertaining life.

Arriving as a young undergraduate at Cambridge in 1930, Burgess developed an enthusiasm for the communist cause when it was entirely fashionable to do so. His talents as a writer and his charismatic demeanor soon caught the attention of Soviet agents who recruited him while he was a postgraduate. As Lownie meticulously documents, Burgess was remarkably successful, supplying the Soviets with plenty of intel and fully disrupting Anglo-American relations in the process.

But the funny thing was – and the author takes care to repeatedly point this out – Burgess didn’t fit the stereotype of a Cold War spy one iota. Flamboyantly gay, conspicuous in the extreme, filthy, disorganized and perpetually inebriated, he so poorly fit the profile that no one could have possibly believed that he was a spy. During his drunken ramblings he would pontificate on communism and politics, even blabbing about his traitorous actions, and no one would be the wiser. In hindsight, it was the perfect cover, even if none of it was intentional.

Presenting a unique look at London during World War II, the book revels in Burgess’ constant drinking and debauchery. Despite the food stains on his clothing and the perpetually dirty fingernails, the man’s life reads like a Who’s Who volume of early to mid-20th century England. WH Auden, Michael Redgrave, Clarissa Churchill, Lucian Freud, Dylan Thomas, Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, John Maynard Keynes, Ludwig Wittgenstein, E.M. Forster, Laurence Olivier and George Orwell to name just a select smattering that I recognized. They all make brief appearances here and there. Burgess knew everybody who was anybody, which may have been the biggest factor in his uncanny success.

Presenting a unique look at London during World War II, the book revels in Burgess’ constant drinking and debauchery. Despite the food stains on his clothing and the perpetually dirty fingernails, the man’s life reads like a Who’s Who volume of early to mid-20th century England. WH Auden, Michael Redgrave, Clarissa Churchill, Lucian Freud, Dylan Thomas, Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, John Maynard Keynes, Ludwig Wittgenstein, E.M. Forster, Laurence Olivier and George Orwell to name just a select smattering that I recognized. They all make brief appearances here and there. Burgess knew everybody who was anybody, which may have been the biggest factor in his uncanny success.

The book also sheds some light on the preposterous nature of Cold War spy craft. Our people would sneak information to their people. Their people would also provide information to our people. Tit for tat. But don’t forget that no one could actually trust the information they received, because it could be a trick supplied by a double agent. I think there may have even been triple agents out there, switching allegiances at will. In the end, it seems like most of this was simply a game that certain types of bureaucrats really enjoyed. I’m sure that some would accuse me of being too naïve, but it’s hard to control one’s skepticism the more one reads of American, British and Soviet ineptitude. One really has to consider that the Cold War spy industry was actually more silliness than substance, but it makes for great historical drama, no doubt. Maybe a simpler and more open-minded diplomacy could make all this unnecessary someday.

A perfect example of truth being wackier than fiction, Stalin’s Englishman is a consistently entertaining look at one of the Cold War’s crazier characters. Meticulously and exhaustively researched, it’ sure to intrigue any reader who’s interested in 20th century British or Cold War history.

— D. Driftless

Trinity College photo by Rafa Esteve (CC BY-SA 4.0)

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1473627389″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014